Small Sample Inference: A Practical R Tutorial

This is the technical companion to Inference Under Scarcity. That post tells the story; this one shows you how to actually do the analysis. If you’re facing a small-sample problem in practice, this is where to start.

I’m going to walk you through a realistic scenario, show you what works (and what doesn’t), and give you code you can adapt for your own data. Along the way, I’ll explain the statistical intuition behind each method—because running code you don’t understand is a recipe for trouble.

The scenario: A pilot gone wrong (or right?)

Here’s the situation. A colleague ran a pilot study testing different versions of an intervention—varying the components, dosages, and delivery methods. Good experimental thinking. But by the time they crossed all the factors, they had 19 treatment arms with barely 5-10 participants in each.

We’ll simulate data that looks like this. I’m rigging the simulation so that most treatments do nothing, but arms 17, 18, and 19 have real effects of 0.8, 1.0, and 1.2 standard deviations. These are large effects—the kind you’d actually hope to detect. Small effects are simply invisible at this sample size.

set.seed(42)

n_per_arm <- sample(5:10, 19, replace = TRUE)

arm <- factor(rep(1:19, times = n_per_arm))

n_total <- length(arm)

# Most arms are null; arms 17-19 have real effects

true_effects <- c(rep(0, 16), 0.8, 1.0, 1.2)

outcome <- rnorm(n_total, mean = true_effects[as.numeric(arm)], sd = 1)

dat <- data.frame(arm = arm, outcome = outcome)Here’s what we’re working with:

Sample sizes per arm:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19

5 9 5 5 6 8 6 6 5 8 5 9 10 8 6 6 7 5 5

Total N: 124124 people spread across 19 arms. Some arms have only 5 observations. The signal-to-noise ratio is terrible. This is exactly the situation we need to learn how to handle.

Part 1: The first question—Is there anything here at all?

Before we start comparing individual arms, let’s ask a simpler question: is there any evidence that the arms differ at all? If the answer is no, we might stop here. If yes, we have permission to dig deeper.

This calls for an omnibus test—a single test of whether all arm means are equal. The classic approach is ANOVA, but ANOVA has problems with small samples. It assumes normally distributed residuals with equal variance across groups. With only 5 observations per arm, we can’t verify these assumptions, and the test loses power.

Enter permutation testing

Permutation tests sidestep distributional assumptions entirely. The logic is beautifully simple:

-

Calculate your test statistic (here, the F-ratio from ANOVA). This is what you observed in your actual data.

-

Simulate the null hypothesis. If treatments truly have no effect, the label attached to each outcome is arbitrary. Person A got treatment 3, but they’d have the same outcome under treatment 7. So shuffle the labels randomly.

-

Recalculate the test statistic on the shuffled data. Record it.

-

Repeat thousands of times. This builds a null distribution—what F-values you’d expect if treatment labels were meaningless.

-

Compare your observed F to the null distribution. If your observed F is larger than 95% of the permuted F-values, that’s evidence (at α = 0.05) that something real is happening.

The beauty is that this makes no assumptions about the shape of your data. The only assumption is exchangeability under the null—that observations are interchangeable when treatments don’t matter.

perm_omnibus <- function(data, nperm = 5000) {

# Step 1: Calculate observed F-statistic

obs_F <- summary(aov(outcome ~ arm, data = data))[[1]]["arm", "F value"]

# Steps 2-4: Build null distribution by shuffling

perm_F <- replicate(nperm, {

data$arm_perm <- factor(sample(as.character(data$arm)), levels = levels(data$arm))

summary(aov(outcome ~ arm_perm, data = data))[[1]]["arm_perm", "F value"]

})

# Step 5: Calculate p-value

p_value <- mean(c(obs_F, perm_F) >= obs_F)

list(observed_F = obs_F, p_value = p_value)

}

omni <- perm_omnibus(dat, nperm = 5000)Result:

Observed F: 1.068

Permutation p-value: 0.393The omnibus test sees nothing. But wait—we know there are real effects in arms 17-19. What gives?

This is small samples for you. An F of 1.07 is indistinguishable from random shuffling. The noise from having only 5-10 observations per arm completely drowns out the signal from three arms with genuine effects. That’s not a bug; that’s statistics being honest about what our data can tell us.

Do we give up? No. We just stop pretending we’ll find certainty here.

Part 2: Okay, but which arms should I follow up on?

The omnibus test told us we can’t claim any arm is definitively different. But maybe we’re asking the wrong question. For a pilot study, we don’t need certainty—we need prioritization. Which arms are most worth following up?

This is where we shift from confirmation to screening. We’re not trying to prove anything. We’re trying to rank our options and identify the most promising candidates for a future, properly-powered study.

Pairwise permutation tests

We’ll compare each treatment arm to control (arm 1) using the same permutation logic. For each comparison:

- Calculate the observed mean difference (treatment minus control).

- Pool all observations from both groups.

- Randomly split them into “treatment” and “control” piles of the original sizes.

- Calculate the mean difference for this permuted split.

- Repeat thousands of times.

- The p-value is the proportion of permuted differences as extreme (in absolute value) as what we observed.

The multiple testing problem

Here’s the catch. We’re making 18 comparisons (arms 2-19 vs. control). Even if all treatments were null, we’d expect about 1 false positive at α = 0.05 just by chance. With more comparisons, it gets worse.

There are two philosophies for handling this:

Bonferroni controls the probability of any false positive across all tests. It’s extremely conservative—to claim significance at α = 0.05 with 18 tests, you need a raw p-value below 0.05/18 ≈ 0.003. With 5 observations per arm, you’d need absolutely enormous effects to hit that threshold.

FDR (False Discovery Rate) controls the proportion of false positives among your discoveries. If you flag 10 arms and accept 10% FDR, at most 1 of those 10 is expected to be a false lead. This is less conservative and more appropriate for screening, where you’re going to follow up on hits anyway.

The Benjamini-Hochberg FDR procedure ranks p-values and adjusts each based on its rank. Smaller p-values get smaller penalties. The raw p-values give you the ranking (which arms look most promising); the FDR-adjusted p-values help you set a threshold for follow-up.

pairwise_perm_vs_control <- function(data, control = "1", nperm = 5000) {

arms <- setdiff(levels(data$arm), control)

ctrl <- data$outcome[data$arm == control]

res <- lapply(arms, function(a) {

trt <- data$outcome[data$arm == a]

obs_diff <- mean(trt) - mean(ctrl)

# Pool and permute

pooled <- c(trt, ctrl)

ntrt <- length(trt)

perm_diffs <- replicate(nperm, {

sh <- sample(pooled)

mean(sh[1:ntrt]) - mean(sh[(ntrt + 1):length(pooled)])

})

# Two-sided p-value

p_raw <- mean(abs(c(obs_diff, perm_diffs)) >= abs(obs_diff))

c(arm = a, diff = obs_diff, raw_p = p_raw)

})

out <- as.data.frame(do.call(rbind, res))

out$raw_p <- as.numeric(out$raw_p)

out$diff <- as.numeric(out$diff)

out$FDR_p <- p.adjust(out$raw_p, method = "fdr")

out[order(out$raw_p), ]

}

pairwise_results <- pairwise_perm_vs_control(dat, control = "1", nperm = 3000)Here’s what bubbles up:

| Arm | Difference vs Control | Raw p-value | FDR-adjusted p |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | +1.68 | 0.015 | 0.28 |

| 9 | +0.87 | 0.115 | 0.75 |

| 7 | +0.64 | 0.191 | 0.75 |

| 14 | +0.63 | 0.253 | 0.75 |

| 18 | +0.67 | 0.257 | 0.75 |

| 17 | +0.50 | 0.285 | 0.75 |

Look at where our true signal arms landed: 19 is #1, 18 is #5, 17 is #6. They’re in the top third, but they’re swimming with imposters (arms 9, 7, 14 are all noise that happened to look good by chance).

Arm 19 stands out—biggest effect (+1.68), lowest p-value (0.015). But even after FDR adjustment, it’s at 0.28. Not “significant” by any conventional threshold.

This is what honest screening looks like. No declarations of victory. Just a prioritized list with uncertainty attached.

Part 3: What if someone demands a “real” result?

Sometimes you need confirmatory evidence—a result you can stake your reputation on. For that, you need to control the familywise error rate (FWER): the probability of making any false positive across all comparisons.

The Max-T approach (Westfall-Young permutation)

This is tighter than Bonferroni because it accounts for the correlation structure among tests. The algorithm is clever:

-

Compute observed t-statistics for each arm vs. control.

-

Under permutation: Shuffle all outcomes across all arms. Recompute t-statistics for every comparison. But here’s the key: record only the maximum absolute t-value across all 18 comparisons.

-

Repeat thousands of times. You now have a null distribution of “worst-case” t-statistics.

-

For each arm’s observed t: The adjusted p-value is the proportion of permuted max-T values that exceed it.

Why does this work? Under the null, the largest t-statistic you’d see across 18 comparisons is what matters for controlling false positives. By calibrating each arm’s p-value against this “worst-case” distribution, you get valid FWER control. Unlike Bonferroni, this automatically accounts for correlations between tests.

The trade-off: Max-T is still strict. It’s for when you need to be certain.

dunnett_maxT <- function(data, control = "1", nperm = 5000) {

arms <- setdiff(levels(data$arm), control)

ctrl <- data$outcome[data$arm == control]

# Calculate observed t-statistics

obs_t <- sapply(arms, function(a) {

trt <- data$outcome[data$arm == a]

nx <- length(trt); ny <- length(ctrl)

sp <- sqrt(((nx - 1) * var(trt) + (ny - 1) * var(ctrl)) / (nx + ny - 2))

(mean(trt) - mean(ctrl)) / (sp * sqrt(1/nx + 1/ny))

})

# Build null distribution of max |t|

maxT_perm <- replicate(nperm, {

perm_y <- sample(data$outcome)

ctrl_p <- perm_y[data$arm == control]

tvals <- sapply(arms, function(a) {

trt_p <- perm_y[data$arm == a]

nx <- length(trt_p); ny <- length(ctrl_p)

sp <- sqrt(((nx - 1) * var(trt_p) + (ny - 1) * var(ctrl_p)) / (nx + ny - 2))

(mean(trt_p) - mean(ctrl_p)) / (sp * sqrt(1/nx + 1/ny))

})

max(abs(tvals))

})

# Adjusted p-values

adj_p <- sapply(abs(obs_t), function(t) mean(maxT_perm >= t))

data.frame(arm = arms, t_stat = obs_t, maxT_p = adj_p)[order(adj_p), ]

}

maxT_results <- dunnett_maxT(dat, control = "1", nperm = 3000)Result:

| Arm | t-statistic | Max-T adjusted p |

|---|---|---|

| 19 | 2.91 | 0.15 |

| 9 | 1.73 | 0.64 |

| 7 | 1.42 | 0.82 |

Nothing clears the bar. Arm 19—the one with a true effect of 1.2 standard deviations—lands at p = 0.15.

The method isn’t broken. It’s doing exactly what it should: telling you that with 18 comparisons and 5 people per arm, you cannot make confirmatory claims. This is the statistical system working as designed.

Part 4: What about blocked designs?

If your experiment has structure—different sites, batches, or time periods—your permutations should respect it.

Why blocking matters

Suppose outcomes at Site A are systematically 0.5 points higher than Site B (due to local conditions, different populations, whatever). If we ignore this and shuffle labels freely across sites, we might attribute site-level variation to treatment effects—or vice versa.

The fix is restricted permutation: only shuffle treatment labels within each block. A participant in Site 3 can only swap labels with other Site 3 participants. This preserves the block structure, ensuring that any block effects cancel out when we compare treatments.

When to use this:

- Multi-site trials (sites = blocks)

- Stratified randomization (strata = blocks)

- Repeated measures or time periods (time = blocks)

- Batch effects in lab experiments (batches = blocks)

# Add some blocks to our data

dat$block <- factor(rep(1:5, length.out = nrow(dat)))

blocked_omnibus <- function(data, nperm = 3000) {

# Include block in the model

obs_F <- summary(aov(outcome ~ arm + block, data = data))[[1]]["arm", "F value"]

# Permute arm labels WITHIN blocks only

perm_F <- replicate(nperm, {

data$arm_perm <- with(data,

unlist(tapply(as.character(arm), block, function(x) sample(x))))

data$arm_perm <- factor(data$arm_perm, levels = levels(data$arm))

summary(aov(outcome ~ arm_perm + block, data = data))[[1]]["arm_perm", "F value"]

})

mean(c(obs_F, perm_F) >= obs_F)

}

blocked_p <- blocked_omnibus(dat, nperm = 3000)

# Result: 0.379Still nothing—but at least we’re not accidentally calling a site effect a treatment effect.

Part 5: Showing uncertainty honestly

Maybe the most honest thing we can do is stop chasing p-values and just show the uncertainty. Confidence intervals do this better than hypothesis tests.

Permutation-based confidence intervals

We can construct intervals using the permutation distribution to approximate sampling variability:

- Pool the treatment and control observations.

- Randomly split them into “treatment” and “control” groups (same sizes as original).

- Compute the mean difference for this permuted split.

- Repeat thousands of times to get a distribution.

- Take the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles, centered on the observed estimate.

Caveat: This is an approximation. For rigorous CIs, use bootstrap resampling (boot::boot.ci()). But for screening, this gives a good sense of the uncertainty.

perm_ci <- function(data, arm_id, control = "1", conf = 0.95, nperm = 3000) {

trt <- data$outcome[data$arm == arm_id]

ctrl <- data$outcome[data$arm == control]

obs <- mean(trt) - mean(ctrl)

pooled <- c(trt, ctrl)

ntrt <- length(trt)

perm_diffs <- replicate(nperm, {

sh <- sample(pooled)

mean(sh[1:ntrt]) - mean(sh[(ntrt + 1):length(pooled)])

})

alpha <- 1 - conf

ci <- quantile(perm_diffs, c(alpha/2, 1 - alpha/2)) + obs

c(estimate = obs, lower = ci[1], upper = ci[2])

}

# Calculate for all arms

treatments <- setdiff(levels(dat$arm), "1")

ci_mat <- t(sapply(treatments, function(a) perm_ci(dat, a)))

ci_df <- as.data.frame(ci_mat)

ci_df$arm <- treatments

ci_df <- ci_df[order(ci_df$estimate), ]Sample results:

| Arm | Estimate | 95% Interval |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | -0.40 | [-1.32, 0.55] |

| 17 | +0.50 | [-0.34, 1.33] |

| 18 | +0.67 | [-0.43, 1.73] |

| 19 | +1.68 | [0.15, 3.21] |

Look at arm 19. The point estimate (+1.68) is close to the true effect (1.2). The interval just barely excludes zero. But it spans roughly 3 units—massive uncertainty. With n=5, this is reality.

The width of a CI scales with $1/\sqrt{n}$. With n=5, intervals are roughly 3× wider than with n=45. This is why small samples produce such uninformative results.

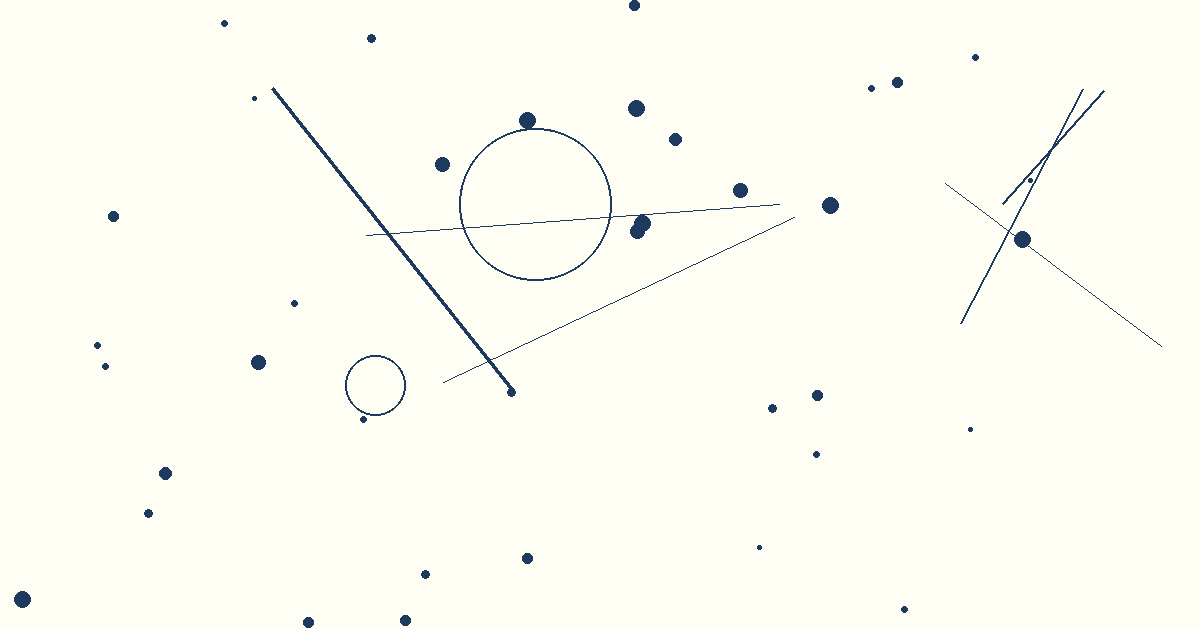

Visualizing everything: Forest plot

A forest plot shows all arms at once—point estimates and intervals on a single axis.

par(mar = c(4, 8, 2, 2))

plot(ci_df$estimate, seq_len(nrow(ci_df)),

xlim = range(ci_df$lower, ci_df$upper),

pch = 19, xlab = "Effect vs control", ylab = "",

yaxt = "n", main = "Permutation confidence intervals")

segments(ci_df$lower, seq_len(nrow(ci_df)),

ci_df$upper, seq_len(nrow(ci_df)))

abline(v = 0, lty = 2, col = "red")

axis(2, at = seq_len(nrow(ci_df)), labels = ci_df$arm, las = 1)Arms to the right of zero (the dashed red line) show positive effects. Arms whose intervals cross zero can’t be distinguished from null at 95% confidence. The width tells you how uncertain each estimate is.

Arm 19 stands out visually—but most arms are indistinguishable from noise.

Part 6: The pooling question—Can we do better?

So far we’ve treated all 19 arms as separate entities. But maybe that’s part of the problem. What if we combine some arms?

The power problem

Power depends on sample size per group. With n=5 per arm, we’re fighting uphill. But if we can combine arms that share a common mechanism (e.g., “high dose” vs “low dose”), we effectively increase the sample size for each comparison.

The danger

Pooling decisions must be made before seeing the data. If you pool arms because they look similar in your data, you’re injecting selection bias. The resulting p-values are optimistic and uninterpretable.

Let me show you both scenarios.

Valid: Pool by design

Suppose we knew before the study that arms 17-19 were “high intensity” interventions. We can pool them:

dat$pooled_arm <- ifelse(dat$arm == "1", "control",

ifelse(as.numeric(as.character(dat$arm)) >= 17,

"signal", "null"))

dat$pooled_arm <- factor(dat$pooled_arm, levels = c("control", "null", "signal"))

# Sample sizes: control=5, null=102, signal=17Instead of comparing 5 participants (arm 17 alone) to 5 (control), we’re comparing 17 participants (pooled signal) to the rest. The standard error shrinks, power increases.

Omnibus p-value: 0.050

Signal vs control: p = 0.077We’re right at the edge. Not quite significant, but we’re getting somewhere.

More aggressive: Binary comparison

Pool everything that isn’t signal:

dat$binary <- ifelse(as.numeric(as.character(dat$arm)) >= 17, "signal", "other")

# Sample sizes: signal=17, other=107

# Signal vs Other: p = 0.013Now we’re talking. By collapsing 16 null arms + control into one comparison group, we’ve gained enough power to detect the signal.

This is valid if the pooling was pre-specified based on study design, not observed results.

Invalid: Top vs. bottom (cherry-picking)

Let’s see what happens if we get greedy:

arm_means <- tapply(dat$outcome, dat$arm, mean)

top3 <- names(sort(arm_means, decreasing = TRUE))[1:3]

bot3 <- names(sort(arm_means, decreasing = FALSE))[1:3]

# Top vs Bottom: p = 0.004Wow, p = 0.004! Highly significant!

But this is garbage. We selected the extreme groups after looking at the data. Even if there were no real effects, we’d find a difference between the highest and lowest observed means by construction. This p-value is meaningless.

I’m showing you this because it’s exactly what desperate researchers are tempted to do—and exactly what you must not do.

The pooling lesson

| Strategy | p-value | Valid? |

|---|---|---|

| 19 arms, all separate | 0.39 | ✓ Yes, but no power |

| Top 5 arms (selected on data) | 0.15 | ⚠ Exploratory only |

| Theory-based pooling (3 groups) | 0.05 | ✓ If pre-specified |

| Binary: signal vs all others | 0.013 | ✓ If pre-specified |

| Top 3 vs bottom 3 (selected on data) | 0.004 | ✗ Cherry-picked |

Pooling based on design is science. Pooling based on observed results is p-hacking.

What we learned

Let’s recap. We had 19 arms with real effects hidden in 3 of them:

- Omnibus test: nothing (p = 0.39)

- FDR screening: arm 19 looks promising (raw p = 0.015) but doesn’t survive correction

- Max-T: no confirmatory signals (best p = 0.15)

- Confidence intervals: massive—every arm is compatible with zero

- Pooling by design: finally gets us to p = 0.013

And yet—the ranking worked. Arms 19, 18, 17 (the real effects) landed at #1, #5, and #6 in our pairwise screen. Mixed in with noise, yes. But the true signals floated toward the top.

That’s what you can expect from a screening exercise: imperfect signal, honest about its imperfection.

Quick reference

| Goal | Method | Controls | When to use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Is anything different? | Omnibus permutation | Type I error | First step before pairwise |

| What to follow up on? | Pairwise + FDR | Proportion of false discoveries | Screening/exploratory |

| Confirmatory claim? | Max-T | Familywise error rate | Need ironclad evidence |

| Show uncertainty? | Bootstrap/permutation CI | Coverage | Always—display the intervals |

| Stratified design? | Blocked permutation | Type I within strata | Multi-site or stratified |

| Gain power? | Pre-specified pooling | Type I (if pre-specified) | Arms share mechanisms by design |

The bottom line

There is no magic trick for small samples. What you can do:

- Use permutation tests when parametric assumptions are shaky (they usually are with n < 30)

- Use FDR for screening, Max-T for confirmation

- Show confidence intervals—let readers see the uncertainty

- Pool by design, never by results

- Be honest about what your data can and cannot tell you

The uncomfortable truth is that small samples don’t produce the clean, quotable results that make it into abstracts. But honesty about uncertainty is valuable—especially in a field full of overconfident claims from underpowered studies.